CMS/ATMA: Music School for Tomorrow (2)

I was energized by the Saturday sessions of the CMS/ATMA Virtual Conference, “Music School for Tomorrow— Foundational Educational Training of 21st Century Musicians,” and eager to dig into the Sunday sessions. I was able to attend both “Moving Towards Intercultural, Interdisciplinary, and Integrative Learning in Music Education,” and “Practical Activism in Music Schools.”

Moving Towards Intercultural, Interdisciplinary, and Integrative Learning in Music Education

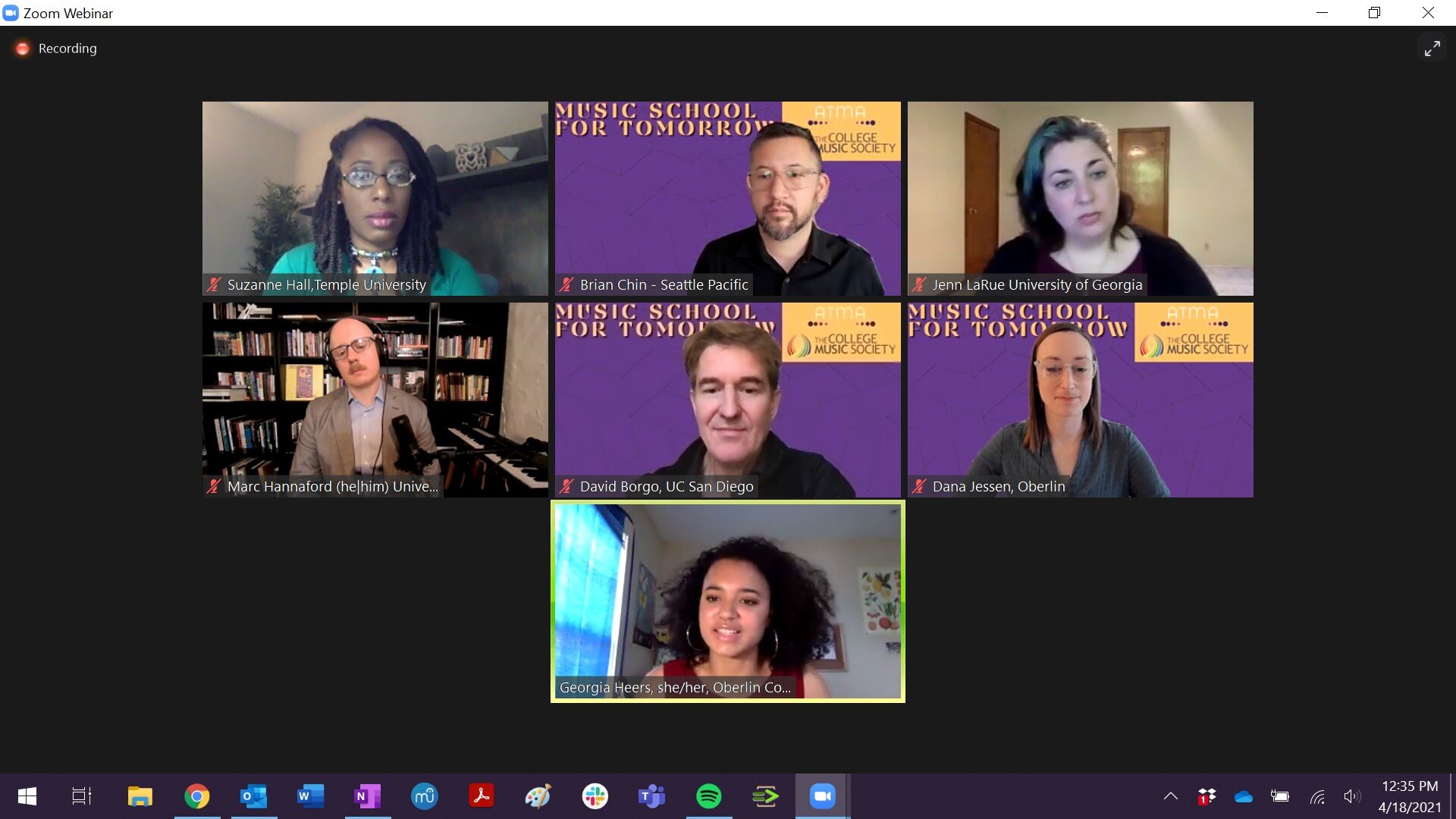

The first session on Sunday was moderated by Georgia Heers and featured panelists Suzanne Hall, David Borgo, Dana Jessen, Brian Chin, Jenn LaRue, and Marc Hannaford.

The assertion that music schools perpetuate white supremacy remained a dominant theme throughout the day. As our conception of “music” includes only a narrow strip of white, Euro-centric styles, so our notions of “excellence” and “expertise” are similarly narrow and culturally biased. That which constitutes “excellence” in "Western music, is fundamentally different from that which constitutes excellence in the Blues, for example. For that matter, even the separation of the “performer” and “composer” into separate entities is inherently Euro-centric. The panel also warned against simply substituting works by Black, non-Western, or women composers into the standard curriculum, as it still privileges Western modes of thought. Epistemological diversity, they argued, was just as important as content diversity. To achieve this, the role of the instructor would need to shift emphatically away from the “sage on the stage” to the “guide on the side.”

Brian Chin, Chair of the Department at Seattle Pacific University, recounted how his faculty had fundamentally reconsidered their goals in light of these idea, and determined that what they really wanted their students to take away were critical or “deep” listening skills, and the ability to appreciate music within its cultural context. “If we can accomplish this,” he concluded, “the content doesn’t matter.” Suzanne Hall remarked that our students, even down to early childhood, come to our programs with extensive musical experiences. Our job is not, then to dismiss this experience and teach them the “right” way to be musical, but to respect and celebrate this experience and facilitate the way they could apply this knowledge. Dana Jessen added that our students aren’t aware of the distance between academia and the "real world"—frequently, only one or two “careers in music” courses were their only point of contact. These approaches would help to narrow that distance.

The panel also acknowledged that in trying to solve such massive, wicked problems, we would inevitably make mistakes, but that this shouldn’t be an excuse for paralysis. They dismissed the common argument that the NASM standards wouldn’t allow such radical shifts: anyone arguing from this perspective, they affirmed, either doesn’t know the NASM standards or has never worked with the association directly. In fact, NASM is very open to new ideas, and does not exist to preserve the status quo.

The first step in making the paradigm shift, the panel agreed, is modelling. Faculty should continue to foster creativity by continuing to perform and compose. They should seek to create spaces where different styles and musics can encounter each other and interact. In their roles as the “guide on the side,” they should also respect the students’ musical identities, and enhance them by demonstrating their connection with other musical experiences. The theme of valuing process over product also pervaded the discussion. In the visual arts, Brian Chin asserted, the “why” always preceded the “how” in faculty critiques, whereas in music the opposite was true. Rather than talking about the student’s musical vision, and then helping them to achieve it, musicians typically begin by criticizing technique and execution. Indeed, they frequently don’t get around to considering the student’s vision.

When the discussion shifted to the “core” courses, the panel generally agreed both reform and abolition were in order. I was particularly charmed by Suzanne Hall’s recommendation to demolish the core… but save the pieces. They also agreed, however, that a fundamental paradigm shift was in order—we couldn’t keep creating more and more elective courses that fewer and fewer students would be able to take. David Borgo’s comment that music is not an object also appealed to me. Rather then thinking of music as a thing that required a “core” to master, he argued, we should think of music as a verb, and engage students in “musicking”

Marc Hannaford, a music theorist, also argued that we should let go of common assumption in Western theory that pitch was the most important element in music. Student could benefit a great deal, he continued, from studies of rhythm and timbre. Like David Borgo’s conception of music as a verb, Marc Hannaford asserted that theory should open doors for students, and always be connected to the creation of music. He was particularly interested in the ability of theory to create abstract structures which then had to be learned and practiced to be fully understood (he cited Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” as an example).

A final thought, which I very much appreciated, was that we should make sure to argue to our administrators that music is more than just concerts—that is a vital, central aspect of the human experience.

Practical Activism in Music Schools

The second session on Sunday was also moderated by Georgia Heers and featured panelists Sachet Watson, Katie Leonard, Alexa Smith, Imani Mosley, and Rikki Morrow-Spitzer. All five women were DEI specialsts, and the session considered a variety of topics surrounding effecting substantive change.

The session opened with a consideration of the meaning of “practical” in “practical activism.” While the term suggests, as Rikki Morrow-Spitzer described, “goal-oriented,” and “with a clear path to achievement,” the ensuing discussion unpacked the concept much further. Alexa Smith discussed the contrast between activism and politics, and emphasized the need for choosing the right time, finding shared values, etc. Katie Leonard contrasted activism with organization, describing the former as short-term/abstract and the latter as long-term/concrete. Finally Imani Mosley meditated on how the “practical” is frequently defined in terms of its opposite. It is frequently easier to define the impractical (“what can’t be done”), she asserted, but this is defined largely by the imagination: the practical is defined by what people feel is impractical. In fact, the space for practicality is larger than we imagine, and if we can demonstrate the practicality of an idea, it is much easier to subvert any opposition.

Sachet Watson mused on the difficulty of being a member of the institution you're trying to dismantle, and explained her approach through a Jenga metaphor. In Jenga, she explained, the object is not to win, but to make your opponent lose. If the system of oppression is like the tower of blocks, an effective strategy is to remove all the loose blocks: in our case, curricular changes, instituting a holistic approach to teaching, studying oppression, and so forth, until only the load-bearing blocks are left. At this point, the institution has no option but to “fall”; that is, they will be forced to adopt new policies.

Katie Leonard asserted that, in higher education generally, we tend to think we're further along in anti-racism than we actually are. The high-sounding declarations, committees, and task forces look good, but often have no real authority. Alexa Smith recommended keeping the conversation among the key administrative players until the ideas were clearly understood, and save committees for the implementation phase. The students, she observed, are more ready for change than the faculty and administration. Imani Mosely then observed, that our biggest problem is actually that the system works: the institutions of higher education have been largely successful in spite of their institutional racism, and accordingly, tend to continue as they always have.

The previous conference session had generally extolled the special agency of students in effecting change, but Rikki Morrow-Spitzer was more wary, commenting that we only have them for a short time. The importance of faculty and staff who would stand up for equity was still vital to lasting change. She quoted a mentor, saying “it’s not a sprint or a marathon—it’s a relay.”

When asked what specific changes they’d like to see in higher ed, the panel mentioned the folloiwng

Curriculum reform

Pay equity

Equitable hiring practices

De-centering whiteness

De-centering able-ness

The panel was particularly passionate about the last item, and especially as it related to “invisible disabilities” like anxiety, depression, etc.

Finally, two themes that caught my attention were the panel’s unanimous opposition to tenure, and white supremacy’s celebration of the individual over community. As regards the former, the panel made several compelling observations about the worst abuses of the tenure process. They decried the tendency of institutions to weed out instructors even before the process begins, thus homogenizing the pool of tenure candidates; doubted whether the qualifications for tenure had been reviewed for cultural bias, and what questioned what qualifications were required for members of tenure and promotion committees. Furthermore, they argued that, once awarded, tenure reduced accountability and could potentially protect harmful people in continuing to do harm.

As regards the latter, they observed that music schools were notorious for promoting a harmful version of extreme individualism: self-isolation in practice rooms and single-minded work to the detriment of even basic self-care are typically encouraged and frequently rewarded. As a conservatory graduate, this sounded all too familiar, as did the comment that many students have to “escape” the conservatory in order to “put themselves back together.” In addition to myself, I know several people who have had exactly this experience, (and they don’t even include the people who endured constant verbal and sexual abuse at the hands of their instructors). A final question, “what if the narrative was the well-being of the students?” resonated strongly with me.